Last week I had the chance to participate in the SANS Interactive Beginner Challenge CTF as part of a qualification round for the SANS Security Training Scholarship by Women in Cybersecurity (WiCyS). [Edit: I also made it forward to the next round!] This was a closed, Jeopardy-style CTF that ran for four days (Aug 7-10). It was also a solo CTF, although we did have a Slack channel where people occasionally shared hints to especially hard-to-solve problems.

For each challenge I’ll be sharing a short description of the problem, steps I took to solve it, a list of tools I used, and the flag itself. Since this is a beginner CTF, I tried to explain/link the tools (especially the command-line ones, as indicated in code) I used.

If you’re interested in seeing a particular challenge, open the menu to navigate by headings. They are organized by “difficulty” as listed on Tomahawque.

A note on tooling: my setup is a Windows 10 computer with WSL2 enabled, and for these challenges I was using Google Chrome and Windows Terminal in a zsh prompt. I also occasionally used Visual Studio Code to view un-minified Javascript files.

Special thanks to Ruju Jambusaria, Saba A, and Jodi Rehlander for their hints during these challenges!

Edit: Thank you also to Catherine Chamnankool for her screencap of the C01 challenge! You can see Catherine’s writeup of this CTF on Medium.

This was my first time doing a CTF writeup! If you have a question or comment about this write-up, feel free to reach out to me on Twitter @commitsbyjoyce.

W01

This challenge took us to a website “LingoFlow” for learning languages, that contained a flag somewhere. The description hinted at using the Developer Tools to find the flag.

Things I tried:

- Looking in the source code (by pressing Ctrl+Shift+I) for flags

↪ Unfortunately the only ones available were country ones, though - Submitting the correct answer to the quiz

↪ Only reloaded the page

This took me a really long time to solve (despite being “easy”!), but eventually I was given the tip (h/t Ruju) to look inside the dev console.

Tools: Chrome Dev Console

Flag: Consolel0ggr3

A01

This challenge consisted of a zip file, which when unzipped, gave a photo of a white man with Morse code in the top-left corner.

Using a Morse code converter, we get the following result:

Tools: Morse code converter

Flag: MORCEFORCE#

Further reading: Google offers a Morse code keyboard and learning site that are quite fun and easy to move through!

FE01

This challenge consisted of a zip file, which when unzipped, gave a Rich Text Format entitled document.rtf.

I struggled with this one a lot too - until I was tipped that I can change the text colour (lol - thank you again, Ruju). Doing so reveals the flag at the bottom of the document.

Tools: Microsoft Word

Flag: 𝑛𝑖𝐶𝑒𝐴𝑛𝐷𝐸𝑎𝑠𝑦10018

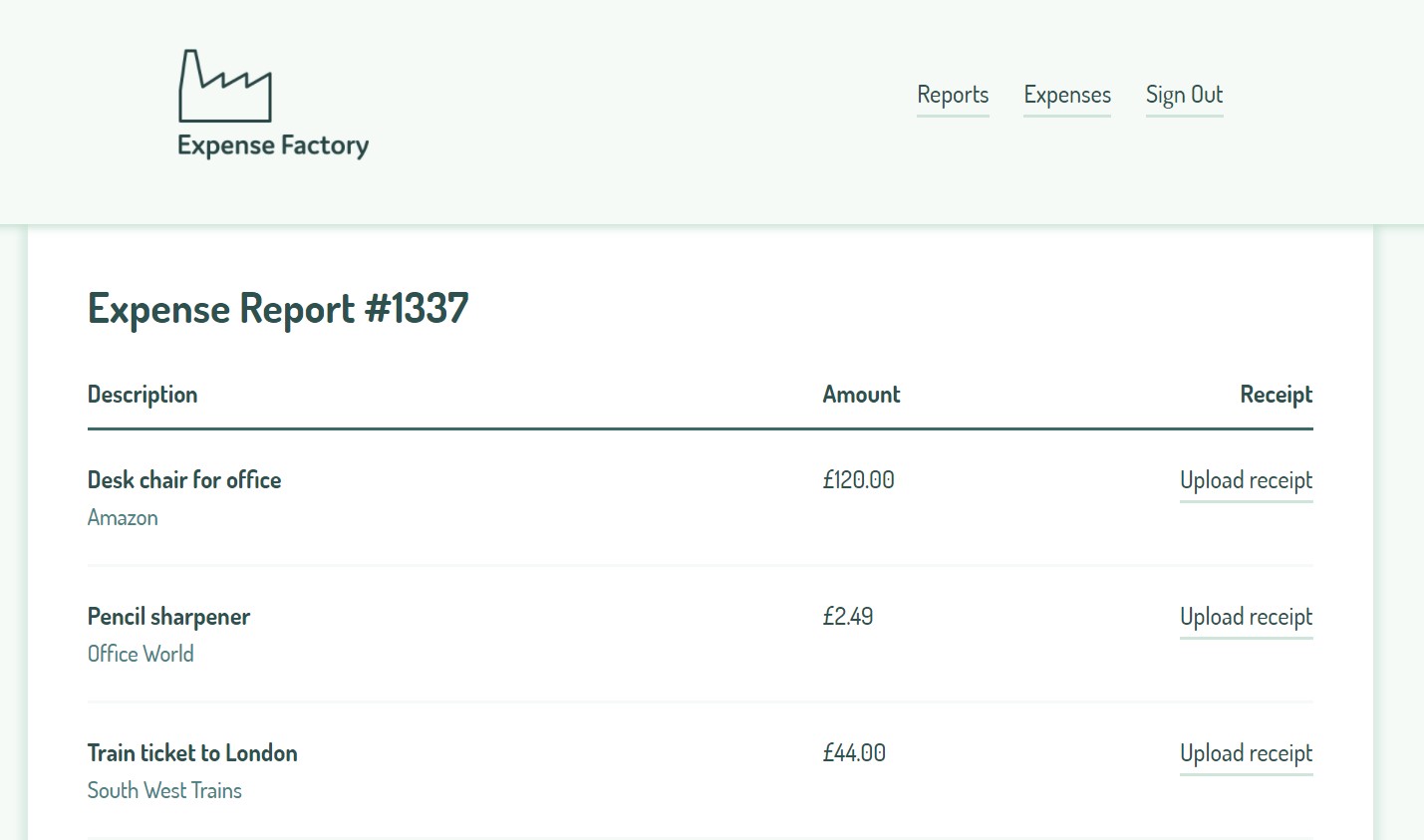

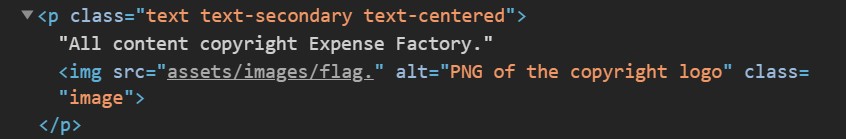

W03

This challenge took us to a website “Expense Factory” which appears to allow users to upload receipts for workplace expenses. The description hinted that we would need to fix something on the site in order to reveal the flag.

My first instinct is to just scroll through the page. At the footer, I spot the following:

Examining the source code more closely, it’s clear that someone left off the png extension when linking to the copyright logo - and that logo is exactly what we need:

Adjusting the linked asset to be assets/images/flag.png reveals the image:

Tools: Chrome Dev Tools

Flag: FIXINGBROKENL1NKS

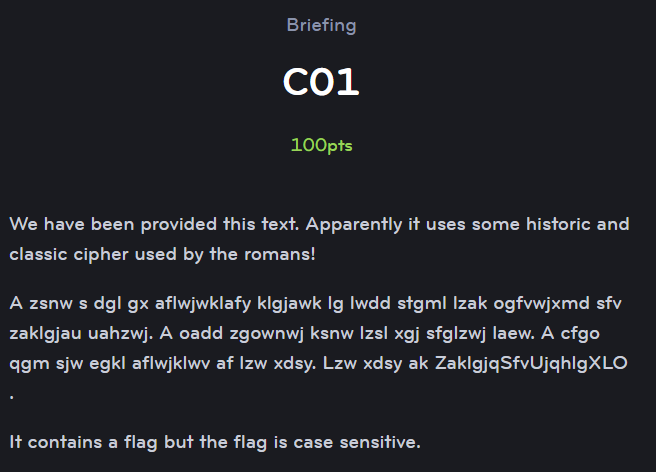

C01

Unfortunately the challenge description was essential here: it contained the ciphertext needed to obtain the flag. The description also hinted that the method used here is related to a famous Roman.

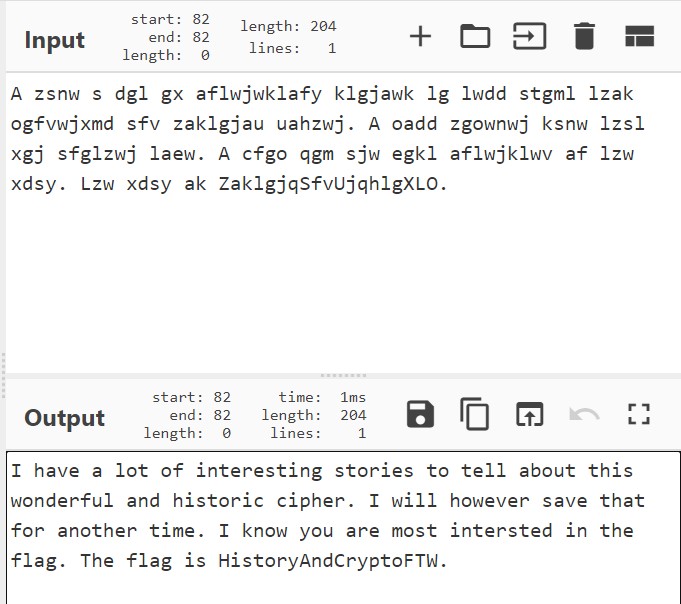

The famous Roman really gives it away here, but the ciphertext is encoded using a Caesar cipher; in particular, ROT13. Using any Caesar cipher decoder will reveal the flag.

Edit: Thanks to Catherine C., I now have a screencap of the original challenge!

The ciphertext is: A zsnw s dgl gx aflwjwklafy klgjawk lg lwdd stgml lzak ogfvwjxmd sfv zaklgjau uahzwj. A oadd zgownwj ksnw lzsl xgj sfglzwj laew. A cfgo qgm sjw egkl aflwjklwv af lzw xdsy. Lzw xdsy ak ZaklgjqSfvUjqhlgXLO.

Fortunately, thanks to the hint, we know that we should be using a Caesar cipher (or shift cipher). Using a shift of 8, we get the following:

Which gives us the flag easily.

Tools: Caesar cipher decoder

Flag: HistoryAndCryptoFTW

Further reading: Caesar ciphers don’t just refer to ROT13 - in fact, it’s any “shift” cipher. Also, ROT13 is its own inverse (since the alphabet is 26 letters long).

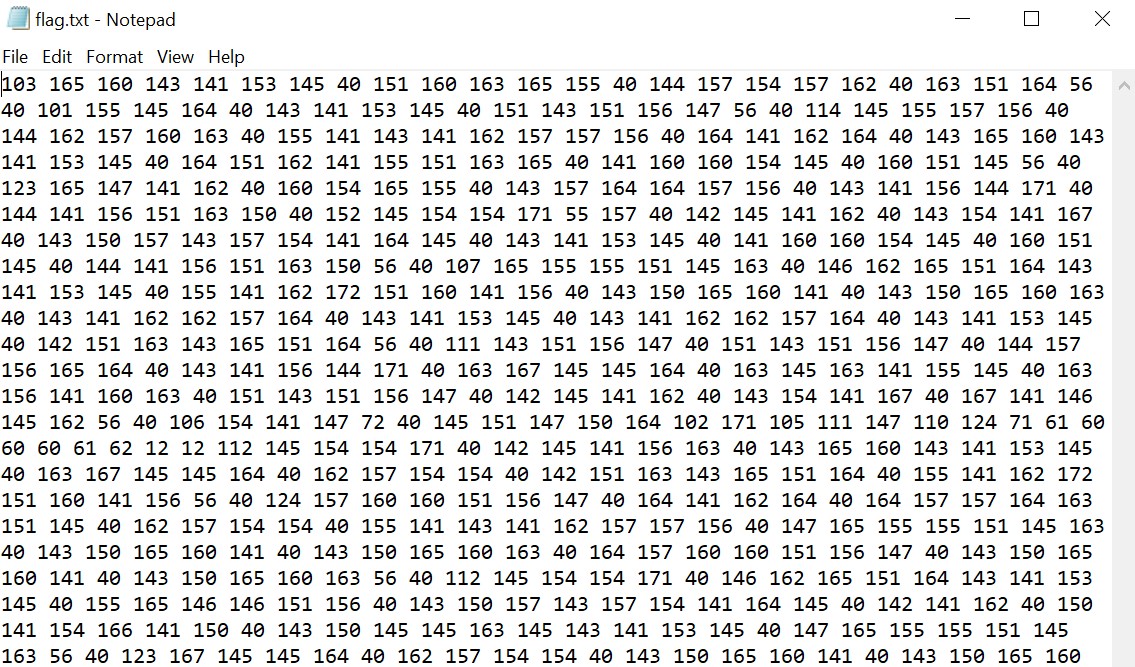

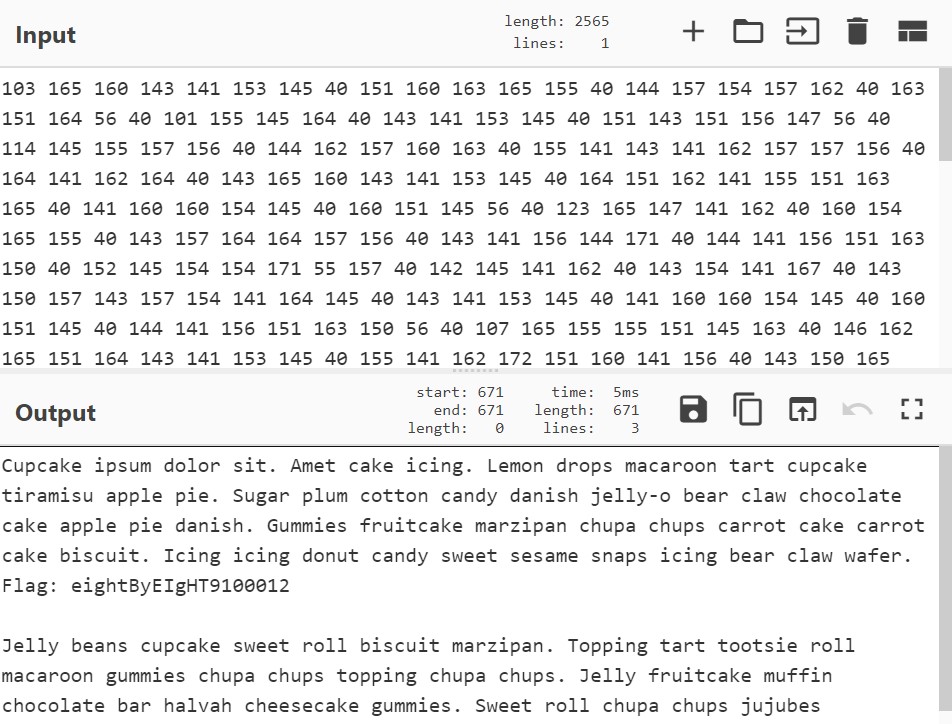

CE01

This challenge was another zip file, which contained a single file flag.txt. Opening this file in Notepad shows a bunch of numbers:

Notice how each number is never more than 3 digits long, and each number never uses the digit 9. This format reminds me a lot of hexadecimal formats, but because the number 9 (or letters A-F) are never used, it has to be a lower base. Another common base is octal (base 8), although I wasn’t aware it’s used for text encoding.

Using an octal to text converter, I get the following result:

Sweeeeeeeeeeet.

Tools: Octal to Text converter

Flag: eightByEIgHT9100012

FE02

Yet another zip file challenge! This zip contained a PDF file entitled document.pdf, while the challenge description noted that the PDF’s layers were still intact.

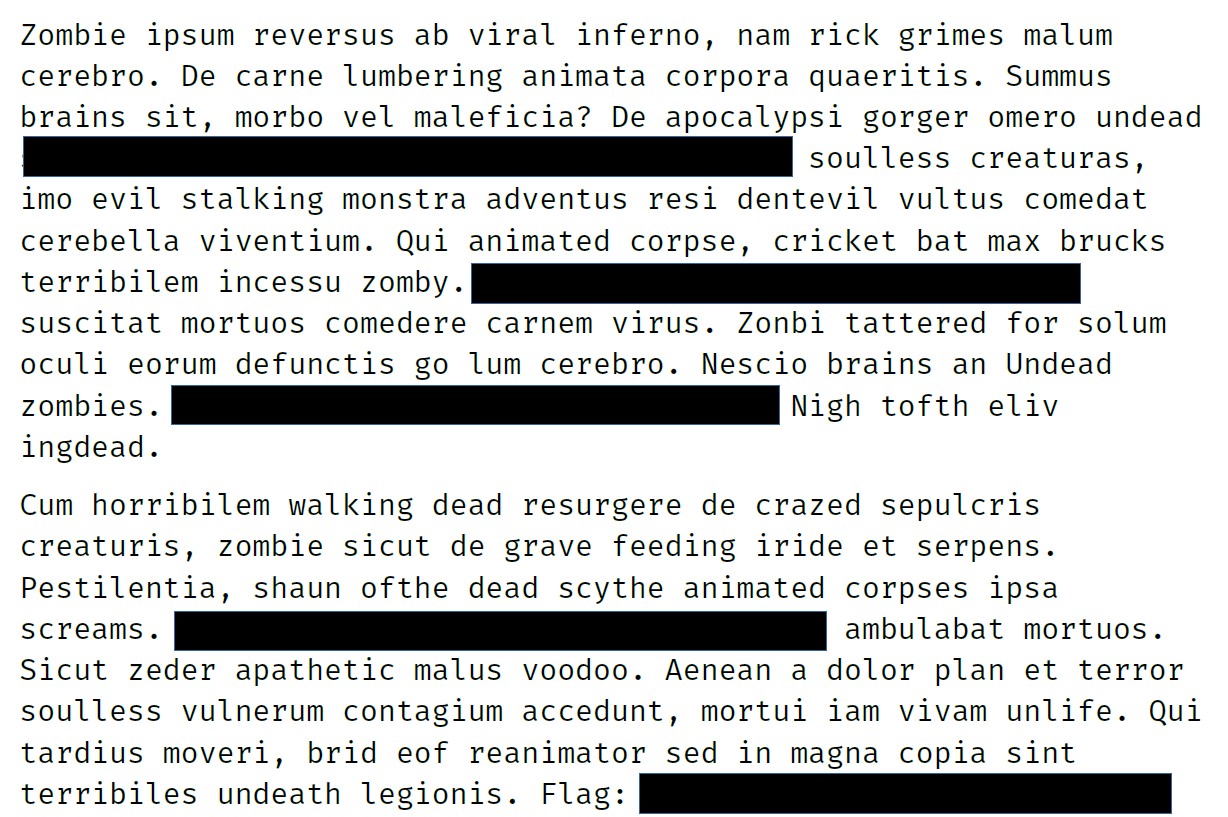

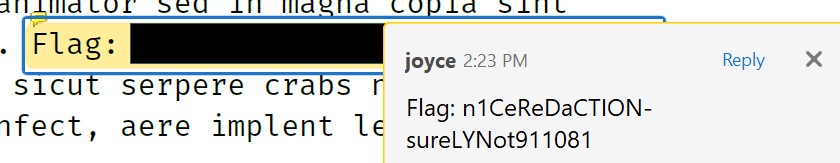

Opening the file in Adobe Acrobat Reader, we see immediately that some of the words/phrases in the PDF have been redacted - including the Flag:

Given the hint, the first thing I try to do is try and “hide” the top layer of redacted marks. However, opening the layers panel in Adobe shows me there are no layers.

However, playing with the PDF a bit more, I realise you can still select the “redacted” text. Here, I’ve copied it to my clipboard and added it as a note to make it more visible:

Tools: Adobe Acrobat Reader (really, any PDF tool)

Flag: n1CeReDaCTION-sureLYNot911081

L01

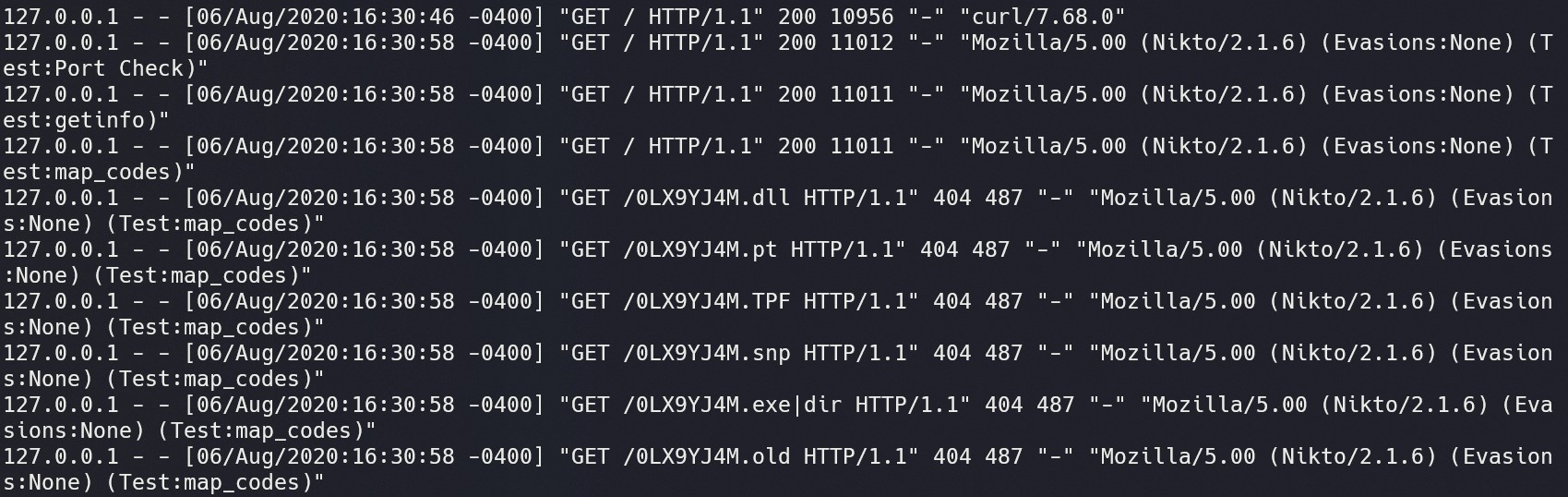

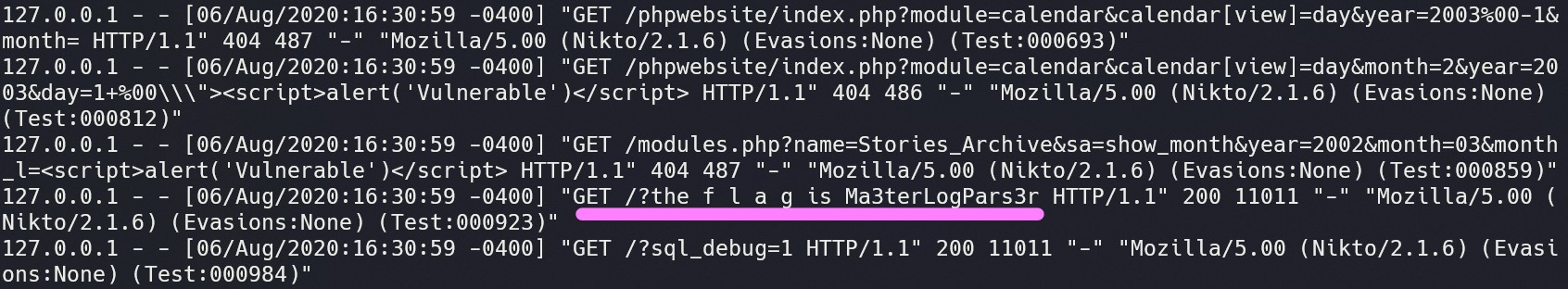

More zip files! This challenge zip contained an access log access.log to a webserver, and the description told us to look at the “200” HTTP responses to find the flag.

Knowing this, I’m going to use grep, a tool which “prints lines matching a pattern” and less, a tool which allows you to view and navigate text files.

By running grep "200" access.log | less, we can view our search for “200” easily navigate through the results using j and k as down/up arrows respectively. This is still a lot of content, but moving down we find:

Looking back, using grep "f.l.a.g" access.log | less would have been much more efficient, since we can use regular expressions to our advantage. However, it wasn’t clear before grep-ing that the flag would be masked!

Tools: grep, less

Flag: Ma3terLogPars3r

Further reading: The logs mention CVE-2014-6271 several times, and many of the 404 results are directed towards 0LX9YJ4M with a variety of extensions. As of yet, unsure as to 0LX9YJ4M's significance.

If you’re curious about regular expressions, Regexr and Regex101 are excellent tools for creating regular expressions and offer references/cheat sheets.

F03

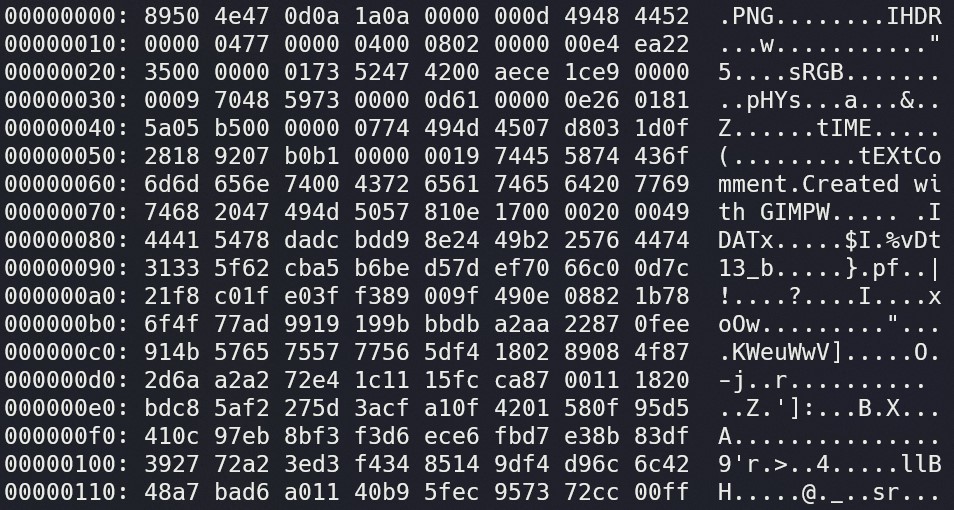

Yet another zip file challenge. This zip file contained a corrupted PNG file, entitled Amazing-PNG.png. Our instructions were to find and fix the image to gain access to the file.

I did not, in fact, fix the file. Actually, what I did was use xxd to create a hexdump of the PNG file, and again use less to navigate the content.

By running xxd Amazing-PNG.png | less, we can see on the left a “line” number, the bytes in hexadecimal format, and an ASCII text translation of the bytes on the right:

Again scrolling through, we eventually find the flag. You’ll notice that it’s much more obvious than the log, because most of the hexdump is sparse garbage, so it doesn’t translate well to ASCII characters.

Tools: xxd, less

Flag: PNGHaxor1337

FM02

More. Zips. This challenge zip gave a program simply entitled file with a corrupted header, and we were told to fix it in order to get the flag.

This one could honestly be its own writeup (similar to WH03) because I spent SO LONG trying to understand it.

Using xxd was pointless, but some other things I also tried doing were:

- Running

file fileto see what kind of file it was (“data”) - Running

readelf -h fileto see whether it’s an ELF file

readelf is used to display information about ELF files (and the flag -h displays the header in particular), and it told me: Not an ELF file - it has the wrong magic bytes at the start.

Well, that’s a start. Wikipedia offers a list of the magic bytes for different file types; for ELF files, that’s 7F 45 4C 46.

Here’s where things get messier. I tried:

- Overwriting the first 4 bytes using

hexedit - Inserting a new row of bytes (which is apparently not possible using

hexedit? So I transitioned to using hexed.it), i.e.7F 45 4C 46appended with0s - Inserting the first 4 bytes, offsetting the existing content

None of these worked. Fortunately, over in Slack, Saba pointed out that the Wikipedia page for ELF files offers an excellent example of a ELF header, which helped guide me to how I should edit this file.

Here I experimented with:

- Overwriting the first two lines with the given header

- Inserting the given header

Both of which didn’t work. However, Jodi pointed out that inserting one line of the header instead might be more beneficial to my cause.

Running this new file then outputted the flag immediately.

Tools: file, hexedit, hexed.it (web), readelf

Flag: headersAreImportANT91-91

Further reading: Magic bytes, ELF files

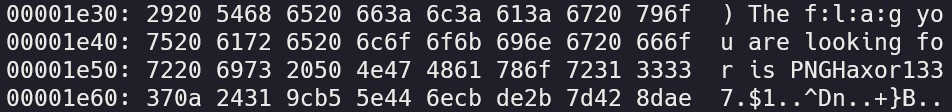

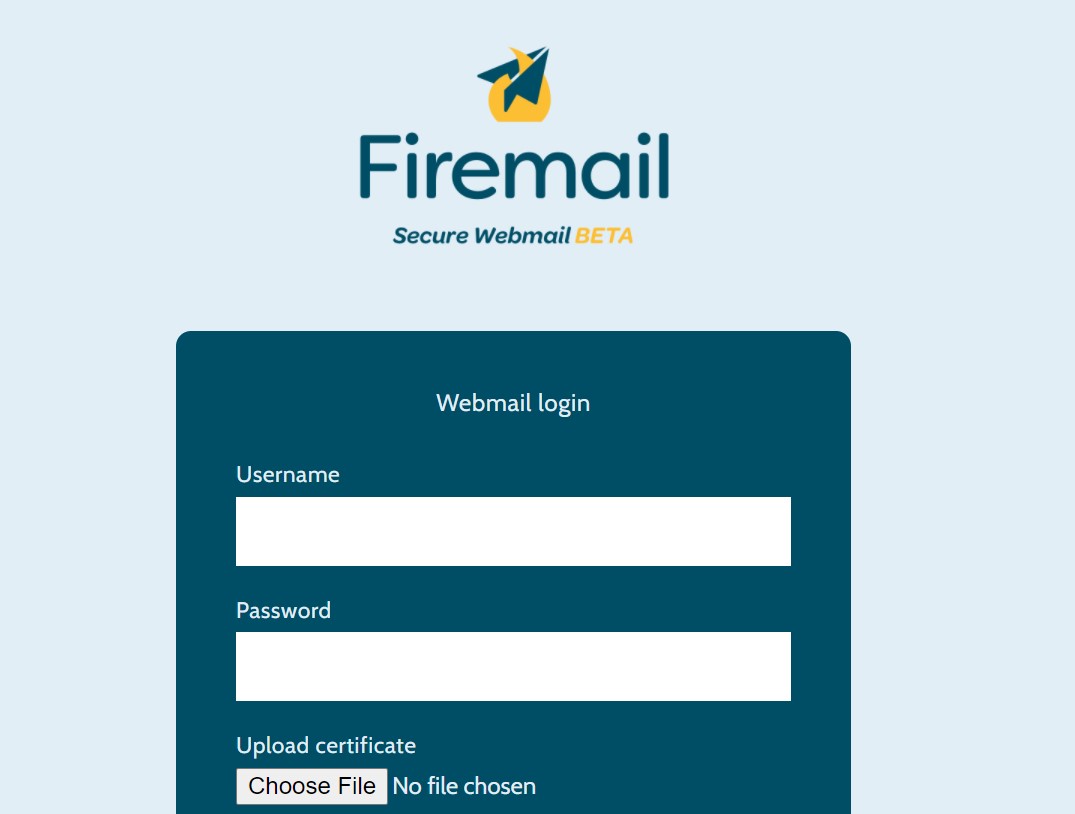

W02

This challenge led us to a website “Firemail”, which featured a login screen with the subtitle “Secure Webmail BETA”. The description told us that the flag would be found within the source code.

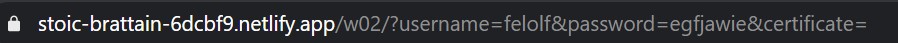

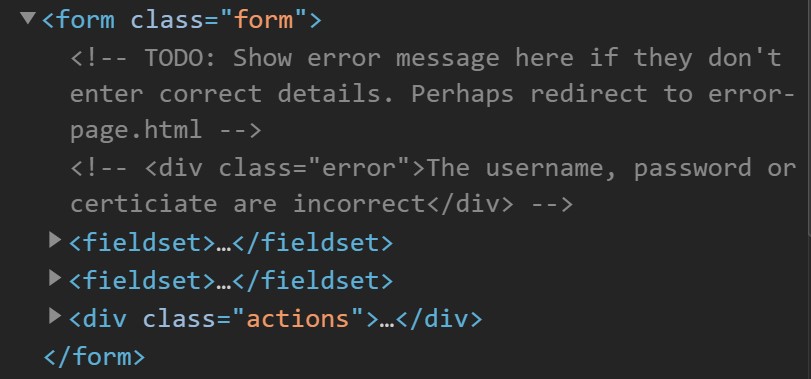

My first thought with login screens is always SQL injection. So I play around with the login screen and try to submit some stuff - obviously I don’t have any certificate to submit, but when I submit garbage, nothing happens either (and the password is exposed, in broad daylight):

In fact, one of the big markers of a vulnerable database is an error popping up that the query is incorrect - and as I submit an empty form, I realise SQL injection is probably not the goal here.

Then I go digging through the source. Turns out their form needs a proper error page:

Navigating to error-page.html on this site then reveals the flag.

Tools: Chrome Dev Tools

Flag: W3bD3buggerLevel1337

Further reading: SQL injections, and how to do them (although not relevant for this challenge)

WE01

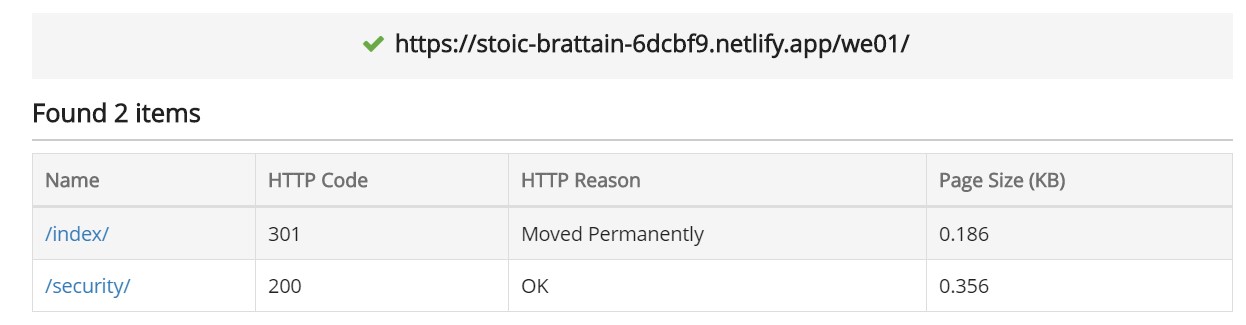

This challenge led us to a website simply titled, “Nothing to see here…” with a GIF of Spongebob furiously fanning flames with his own breath. The description told us that there was a hidden directory where we could then find the flag.

Looking in the source code, it’s pretty barebones. The only hint I’ve got is that the Spongebob GIF belongs in an img/wicys-beginner-ctf/ directory. Navigating to the img/wicys-beginner-ctf/ directory, though, we’re denied access.

This is where I start just trying random directories and hoping for something to stick (it doesn’t). At this point, I get a tip from Ruju to use a tool called URL Fuzzer.

URL Fuzzer allows you to discover hidden directories and files given a domain, which is exactly what we need. Running URL Fuzzer on this website gives us:

Bingo. Navigating to the security directory, we get one entry: flag.txt, which is exactly what we need.

Tools: URL Fuzzer

Flag: verySecUReDireCToRY_1180018

Further reading: On fuzzing, as a testing technique in general

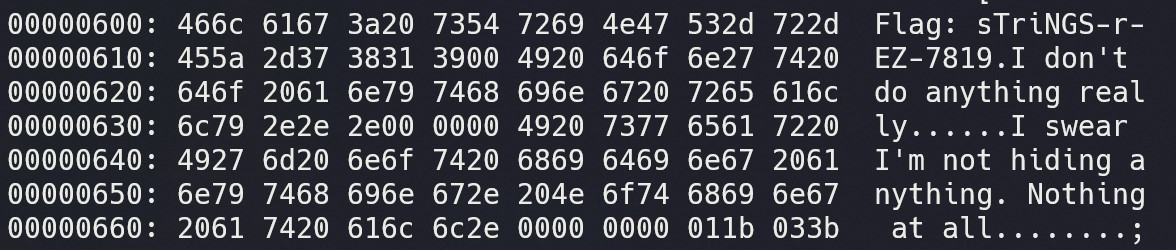

BE01

This challenge brought us back to the zip file. The file contained is a file simply called program; although file program and readelf both declared it to be an ELF file, I had problem running it on my machine.

Fortunately, my old friend xxd was back. Running xxd program | less, like we did with other files before, easily showed the flag with a bit of scrolling:

Tools: xxd, less

Flag: sTriNGS-r-EZ-7819

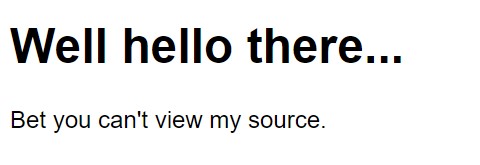

WE02

This challenge brought us to a website that simply taunted, “Bet you can’t view my source”. The description told us that there was a flag hidden in the source code, though - so time to go digging through.

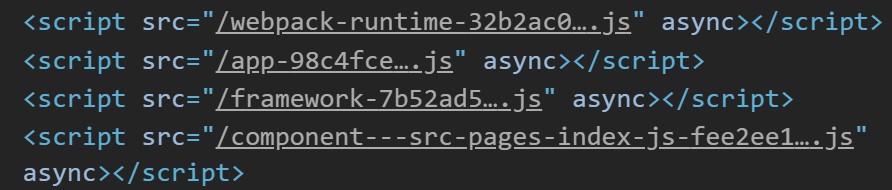

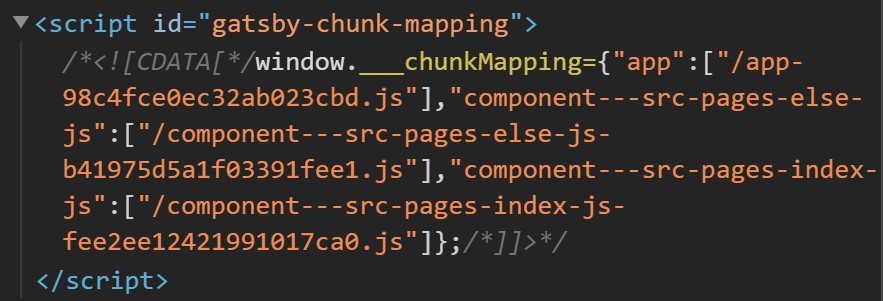

Inside the source, there are four Javascript files linked. As a person who does not speak Javascript, this is not a good sign.

The first two, webpack....js and app....js look like default minified Javascript files.

The third, framework....js is incredibly long and contains two interesting variables, SECRET_DO_NOT_PASS_OR_YOU_WILL_BE_FIRED and __SECRET_INTERNALS_DO_NOT_USE_OR_YOU_WILL_BE_FIRED. To try and understand the file a bit more, I used unminify to make it a bit more readable. I spent a long time in this section, trying to make sense of what, actually, was the internal secret.

The last, component....js simply hinted, “Well I guess the inspector works. I wonder what else is around here.”

So dead ends, all around. Looking back on the homepage, I realise I missed something - just before the four Javascript files is a “gatsby-chunk-mapping” script, which has an array that contains the component....js link and two other similar ones, for else and index.

else sounds pretty darn suspicious, so navigating to that component URL shows the flag immediately.

Tools: Chrome Dev Tools, unminify

Flag: webPACkEd-AlRiGHT_7182

WH03

This challenge leads to a website simply with a blank screen. The description is, really, equally unhelpful.

This, similar to FM02, could honestly be its own writeup. The resulting way I solved it is almost hilarious for how long I stared at this stupid blank screen.

I realized after trying to click random things and trying to type random things, the best way to interact with this is with arrow keys. (Obviously I tried the Konami arrow sequence, but that didn’t go well.)

Sometimes after pressing a key, an arrow will show up:

Other things that can happen when an arrow key is pressed are:

- A change in background colour

- Alerts, saying “Nah”, “So close”, “Maybe next time” and other similar taunts

- A Soundcloud embed of “Never Gonna Give You Ruff”

- A redirect to a Google search of “how to javascript”

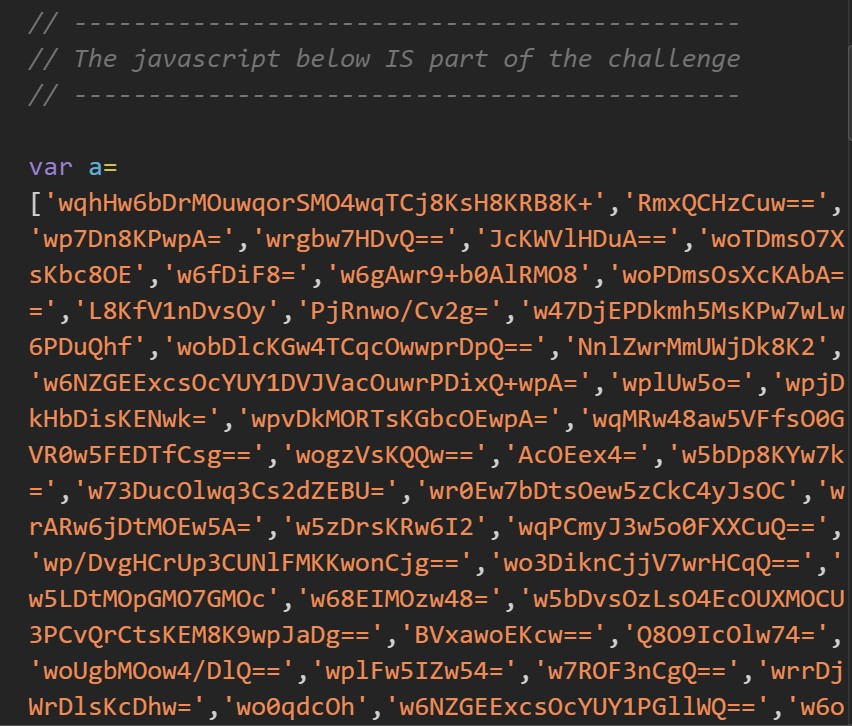

Digging in the source reveals a big long line of minified Javascript, with a line that says “The javascript below IS part of the challenge”.

Obviously the first step, as before, is simply to unminify the Javascript using unminify to try and understand it more.

One of the first things I tried once unminifying it was decoding some of the strings within a (the majorly long array). Many of the strings end in =, which is a common indicator for base64 encoding. However, this proved to be a red herring as a few of the first I tried were simply gibberish and I didn’t have the patience to keep going.

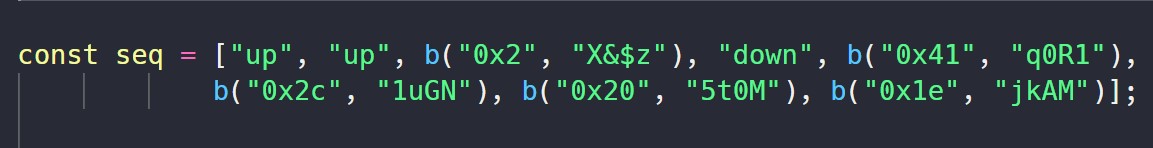

Scrolling through the source code more, I find a variable seq that appears to be an array of arrows, i.e. a sequence of arrow keys to enter.

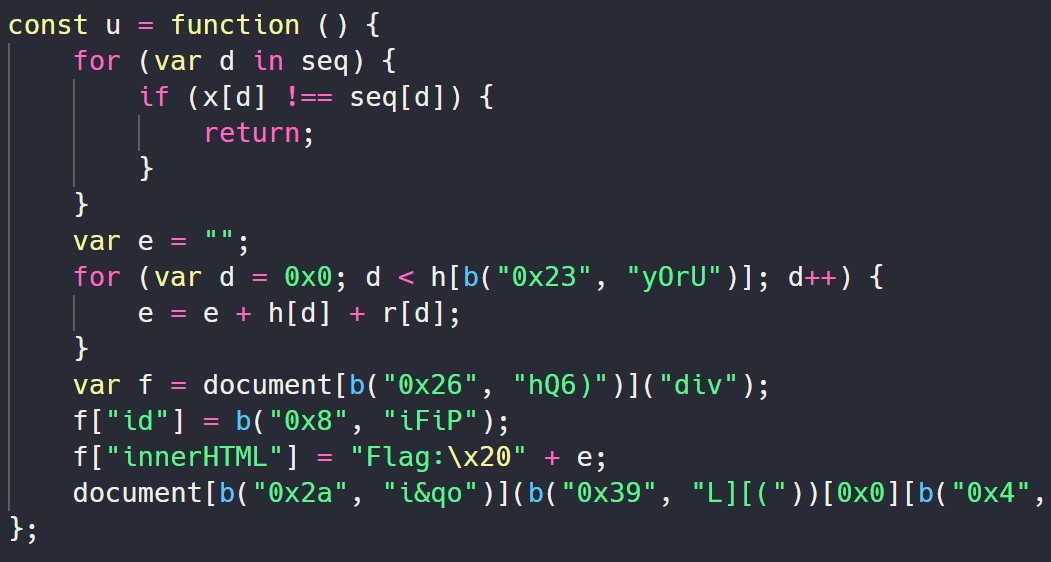

However, I don’t really speak hexadecimal, and looking at the b function is a nightmare in itself. The seq variable is used in this function which prints the Flag:

I eventually ended up coming back to this challenge towards the end of the CTF, and realised that although the console functions are disabled, the console itself isn’t - and a Javascript console essentially acts similar to a Python interpreter. If you give it a variable, it will print the value for you.

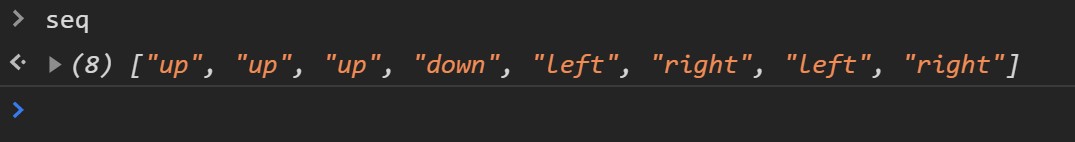

So, naturally, I just printed the seq constant:

However, when I try this, it doesn’t work. No worry - there’s still the flag function to try. The flag function u builds the flag in variable e using arrays h and r.

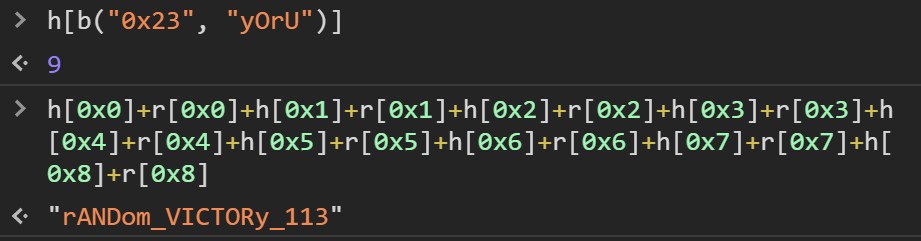

So, I find the value of h[b("0x23", "yOrU")] to see what the ending index is, and then just construct the flag from there:

Tools: Chrome Dev Tools, unminify

Flag: rANDom_VICTORy_113

Conclusion

This was my second CTF ever, and the first where I actually completed all the challenges! Overall I placed 14th out of 449 players, and I’m quite happy with that.

Regretfully I didn’t think of doing a write-up while I was doing the CTF, and the CTF platform Tomahawque does not allow players to view challenges once the event has finished. Thus, screenshots/exact wording of the actual challenge descriptions are limited/non-existent.

Doing this writeup as one long piece after the CTF was also a pain, just because I had to go through the trouble of, basically, redoing all the challenges (with the exception of Caesar) without having access to them! Which made it … difficult.

Overall, I think this was really good for a beginner CTF, just because most of the challenges were relatively easy to understand. My favourite challenges were definitely the ones I could instantly use xxd on - like BE01 and F03. Some challenges were quite hard - FM02 and WH03 in particular - and required a lot more work, but that was good - it gave me a chance to learn more tools! On the whole, it was a positive experience and I’m so glad I got a chance to play.